Leveraging the ADCIRC Model to Plan a Long-Distance, Open-Water Swim from Woods Hole to Martha's Vineyard

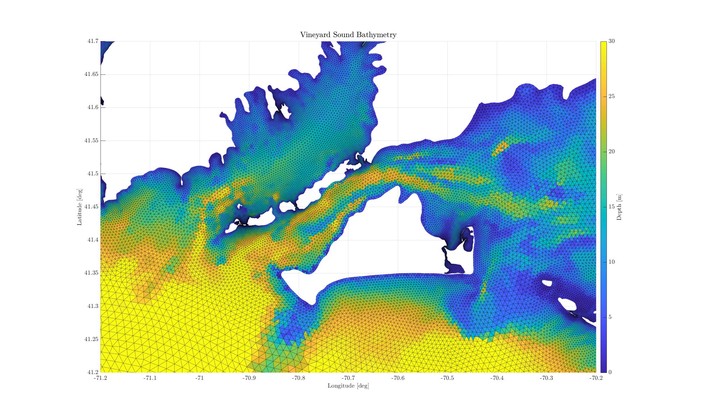

ADCIRC uses bathymetric data, in conjunction with tidally-forced boundary conditions, to predict the flow of water across the computational domain.

ADCIRC uses bathymetric data, in conjunction with tidally-forced boundary conditions, to predict the flow of water across the computational domain.

Preamble

At 5:58am on the morning of July 30th 2022, a small group of swimmers dove into the shallow waters off Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and began swimming steadily southwest toward Martha’s Vineyard. The island was already visible in the early dawn light, though its features were obscured by mist and atmospheric scattering. Lacking terrestrial landmarks, the swimmers would need to orient themselves relative to nearby guide boats in order to make it safely to their intended destination near Lake Tashmoo.

As the crow flies, Martha’s Vineyard and Woods Hole are separated by only 3.3 miles; however, the sea separating these two landmasses is infamously tempestuous, with currents routinely exceeding 5 knots. These strong currents are driven in large part by tidal resonance in the Gulf of Maine, which produces an isotropic pressure gradient between Cape Cod Bay and Buzzards Bay.

A strong ocean swimmer can maintain a speed of 1.4-1.8 knots in ideal conditions, and sprint at 3 knots for a brief time. Thus, it is vitally important that one seeking to swim across Vineyard Sound make a careful accounting of its powerful tidal currents.

The Chappy Swimmers

The genesis of this swim can be traced back to an eclectic cadre of goggle-clad humans who call themselves the Chappy Swimmers. This Falmouth-based swim club is a tight-knit group of long-time friends who range in age from 30 to 70, and simply enjoy swimming together. Rob Thieler, the Center Director of the USGS Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, manages the Chappy Swimmers group text, and is responsible for informing members where they will be swimming each weekend. Rob is one of the eldest members (by seniority, not age), and has been swimming with the group since its founding in the early 1990’s. Anyone can become a Chappy Swimmer – the group is exceedingly friendly and inclusive. One of the regulars named John McCadam started training with the group a few years ago, despite having no formal swim background. He now swims every day, even in the icy winter months when water temperatures routinely dip into the low-30s.

![A small subset of the Chappy Swimmers, featuring: Rick Rheinhardt, Blake Cole, Kalina Grabb, Meri Gilson, Mary Kaminski, and Moira McCollough. [Photo: Chuck Redington]](chappy-swimmers.jpg)

A small subset of the Chappy Swimmers, featuring: Rick Rheinhardt, Blake Cole, Kalina Grabb, Meri Gilson, Mary Kaminski, and Moira McCollough. [Photo: Chuck Redington]

Shockingly, John isn’t the only blue-lipped masochist in the group. Of the thirty or so active summer members, approximately five are gnarly enough to swim through the winter. Sometimes, on cold, dark January mornings, veterans of the group would speak in hushed tones about the time – nearly a decade ago – when they successfully swam across Vineyard Sound. These stories piqued the interest of recent MIT-WHOI Joint Program graduate Dr. Kalina Grabb.

Kalina is an intrepid human. She played collegiate waterpolo, and still carries herself with a subtle alertness that surely grew out of the need to remain calm while grim-faced aquatic gladiators tried to drown her in various chlorinated cerulean coliseums nationwide. However, this quiet intensity is often obscured by her overwhelming geniality. Kalina is one of the nicest people you will ever meet, and has an infectious laugh. She seems capable of weathering life’s most brutal tempests with a smile and a wave. So, in Dr. Grabb, we have a highly-competent swimmer who is both endlessly game for adventure, and affable enough to coax the fence-sitters (including yours truly) into action.

The Plan

In March 2022, a small group of the winter Chappy Swimmers, including John McCadam, Meri Gilson, Mary Kaminski, and Kalina Grabb were out freezing their asses off somewhere in Buzzards Bay when Kalina popped the question: “So who wants to swim to Martha’s Vineyard this year?” A salvo of enthusiastic replies filled the chilly Spring air, echoing off the rows of vacant summer mansions which line the waterfront. A plan had been hatched.

However, a plan once hatched, must be nurtured until it is able to sustain itself, and take flight. Months passed, and the grand plan remained anaemic. In early July 2022, Kalina texted the Chappy Swimmers to alert them that she was serious about the idea, and would be starting a new group chat with anyone interested in participating. One man was particularly interested, and would prove himself invaluable in the planning process: Rick Rheinhardt.

Rick grabbed the ball from Kalina and ran with it.

On July 14th, 2022, Rick sent out a detailed email covering swim logistics, safety concerns, ferry schedules, support boat logistics, and swim date proposals. Long before most people had even seriously considered how messy and complicated this swim could get, Rick had basically already hashed the whole thing out. An excerpt from his email read:

I have been looking at tides and currents in the 2022 Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book… Current information is critical to us because we cannot outswim them, but we can use them to our advantage… There is a countercurrent off MV from Norton Pt to Vineyard Haven that floods NE while the main part of the Vineyard [Sound] ebbs southwest. If we catch [the current] off Norton Point, it will assist us the last 1/3rd of our swim. If we catch it too far North, it could pull us into Vineyard Haven Bay and into the ferry route…. I think we should plan to leave on an ebb tide in Vineyard Sound before slack water at dead low tide. Riding an ebb tide will take us southward and away from most boat and ferry traffic.

![An excerpt from the 2022 Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book, which was used to determine an ideal time to start the swim: a neap ebb tide, just before slack. [Photo: Rick Rheinhardt]](eldridge.jpg)

An excerpt from the 2022 Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book, which was used to determine an ideal time to start the swim: a neap ebb tide, just before slack. [Photo: Rick Rheinhardt]

Rick’s analysis tipped the scales: for the first time, it felt real, and everyone started to believe that the swim was actually going to happen. A target date had been selected: July 30th, 2022. This gave the swimmers two weeks to start conditioning, and to recruit additional support vessels.

The ADCIRC Hydrodynamic Model

Background

On July 20th, I mentioned to my advisor, Dr. Peter Traykovski, that I intended to swim to Martha’s Vineyard in a few week’s time. Peter is an avid waterman himself, and immediately took a keen interest in the endeavor. Understanding the severity of the tidal currents in Vineyard Sound, he inquired as to whether we had developed a detailed plan to contend with these currents. I told Peter that we had narrowed down a set of prospective dates using the 2022 Eldgride Tide and Pilot Book, but still needed a specific swim plan for the day (i.e. a set of waypoints or headings to follow).

Mostly for fun, he suggested I pursue a technical approach, using the output of a tidally-driven, depth-averaged hydrodynamic model of Vineyard Sound to assess the effect of current action on a simulated swimmer. So, I got to work!

In 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) used a shallow-water equation solver called the ADvanced CIRCulation model (ADCIRC) to create a vertical datum transformation tool called VDATUM. The purpose of this tool was to facilitate the comparison of water level measurements made with respect to different vertical references. For instance, some measurements might be made with respect to a tidal datum, like Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW), while others might be made with respect to an orthometric datum, like NAVD88. In order to create this tool, NOAA needed to simulate sea surface levels under tidal action, from the Gulf of Maine south to Rhode Island, over a span of 55 days. For the purposes of this project, NOAA was not particularly interested in tidal currents.

However, the shallow-water equations require the simultaneous computation of water level and flow velocity at each computational grid point. It is useful to look at a simplified 1D form of the shallow-water equations (sometimes called the Saint-Venant equations) to illustrate this point:

$$\frac{\partial A}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial \left(Au \right)}{\partial x} = 0$$

$$\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + u\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} + g\frac{\partial \zeta}{\partial x} = - \frac{P}{A} \frac{\tau}{\rho}$$

The first of these equations can be recognized as the continuity equation. Together, these two equations describe one-dimensional flow of an incompressible fluid in an open channel, where $x$ is the spatial coordinate running along the length of the channel; $t$ represents time; $A(x,t)$ is the cross-sectional area of the flow; $\tau(x,t)$ is the shear stress along the wetted perimeter $P(x,t)$; $u(x,t)$ is the flow velocity along the channel axis; and $\zeta(x,t)$ is the free surface elevation.

This is probably a good time to mention that the good folks at NOAA and the USGS really did all the heavy lifting here (specifically, Zizang Yang, Edward P. Myers, Erin Twomey, and Rich Signell): they generated the computational grid; synthesized bathymetric data from multiple sources; interpolated this data onto the computational grid; and used nine tidal constituents to drive the free surface elevation at the model boundaries. ADCIRC handled the rest, predicting the free surface elevation and flow velocity at each grid point over a 55 day span in 2012. The model output was then compared to field measurements to assess its accuracy, and determine appropriate empirical corrections. These corrections were then incorporated back into the ADCIRC model, further enhancing the accuracy of its predictions.

Tidal Constituent Corrections

Due to the fact that tidally-driven currents are periodic in nature, I was able to adapt these ADCIRC model results from 2012 to my application in 2022.

To do this, I needed to complete the following steps:

- Apply a phase offset (nodal phase modulation) and amplitude correction to each tidal constituent. These corrections are dependent on date and latitude.

- Determine the tidal constituent phases corresponding to the morning of July 30th, 2022.

- At each timestep, sum the contribution of each tidal constituent at each spatial grid point.

Fortunately, there is a MATLAB toolbox called T_TIDE, written by Rich Pawlowicz, which facilitates the determination of the relevant tidal constituent corrections. The implementation details of this toolbox are covered in a paper by Rich Pawlowicz, Bob Beardsley, and Steve Lentz, titled Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T_TIDE.

Swimmer Simulation

Once I was able to determine the time-varying vector field of current velocities in Vineyard Sound, I set about simulating the motion of a swimmer. The basic procedure is as follows:

- Specify an initial swimmer position in geodetic coordinates (i.e. latitude and longitude).

- Specify swimmer heading and speed-through-water. These values can be held constant, or dynamically updated over the course of the simulation. This permits the simulation of a swimmer slowing down due to fatigue, or following a non-constant heading.

- Linearly interpolate the ADCIRC current prediction to the swimmer’s position.

- Compute the vector sum of the swimmer velocity and interpolated current velocity to estimate the swimmer’s speed over ground (SOG) and course over ground (COG).

- Using the swimmer’s SOG and COG, solve Vincenty’s Direct Problem to propagate the swimmer position along the WGS84 ellipsoid, and repeat steps 3-5 at each timestep.

Assumptions & Caveats

-

The model timestep was chosen to be $\Delta t = 0.1~hr = 6~min$. This seemed like the shortest time over which a swimmer and guide boat could realistically perceive trajectory errors, and make changes to their course or speed. Additional refinement of temporal resolution would not have been useful. Because I was not actually solving the shallow-water equations, it was not necessary to consider the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition.

-

The spatial resolution of the bathymetric data is not fine enough to fully capture the shallow ridge at Middle Ground. This will likely lead to an underestimation of the tidal current velocity in this region.

-

The ADCIRC model is depth-averaged. This assumption is only valid in circumstances when the horizontal flow velocity is much faster than the vertical flow velocity. This assumption may not hold true in parts of the computational domain where there are rapid changes in bathymetry (like Middle Ground).

-

The Vineyard Sound specific ADCIRC model is driven by barotropic pressure gradients only (i.e. surface set up resulting from tidal action). It does not account for wind shear, nor wave-induced radiation stresses.

Results:

Well, if you made it this far, congratulations! Your reward is a handful of colorful plots and animations.

Recall that the point of all of this was to determine a feasible, effective swim strategy. The three key components of a simple swim strategy include:

- Departure time

- Swimmer speed

- Swimmer heading

Ideally, the modified ADCIRC model would tell us something about how a change in any of these variables changes the fundamental characteristics of the swim, which can be described by:

- Swim duration

- Swim distance

- Arrival destination

Of these three characteristics, swim duration is most important. Assuming the swimmer is providing an approximately constant level of effort, swim duration serves as a good heuristic for fatigue. Conversely, swim distance is less informative. Consider the boundary cases:

- A swimmer opposing a strong current will move nowhere, and nevertheless become completely exhausted after some time.

- A swimmer aided by a strong current could exert no effort, and nevertheless arrive at their destination some arbitrary distance downstream.

For this particular swim, arrival destination is also quite important, as it serves as a heuristic for risk of encountering ferry traffic. Finishing too far to the northeast, near West Chop Point, places one in a strong northeasterly current, directly adjacent to ferry traffic entering and exiting Vineyard Haven Bay. In this region, a small miscalculation could have catastrophic effects.

One final caveat before I dive into the simulation results:

Nothing about what I have done here is “optimal.”

I simply poked around the parameter space (departure time, swimmer speed, and swimmer heading) until I found trajectories that seemed “reasonable.” Specifically, I looked for paths that were:

- Safe. The route must avoid ferry traffic.

- Efficient. The swimmer should not fight the current (mathematically speaking, the dot product of swimmer velocity and current velocity should never be negative).

- Timely. The swim must be completed in less than 2.5 hours to avoid the strongest currents.

- Practical. The swimmer must arrive near the intended destination.

This struck me as a justifiable approach, given that the parameter search space was actually quite small; indeed, Rick had already identified a relatively compact range of feasible departure dates and times. Further, we already knew where we wanted to start (Nobska Beach), where we wanted to finish (Lake Tashmoo), and how fast we could swim. The only remaining unknowns were the exact departure time, swim pace, and where we should point our bodies!

Here is a quick summary of the simulations I ran:

- Constant $145^{\circ}$ Heading

- Forced Transit Through Predefined Waypoints

- Hybrid Strategy: Transit 1st Waypoint + Constant $140^{\circ}$ Heading

- Departure Times

- 6:00a

- 6:18a

- 6:30a

- Swim Pace

- 1:40/100yd

- 2:00/100yd

- Departure Times

Finally, here are a few notes on the animations that might be useful:

- The colormap corresponds to the magnitude of current velocity.

- The black arrows indicate the direction of the current velocity.

- The black lines are rhumb lines between predefined waypoints, represented by black circles.

- The dashed magenta line represents the swimmer trajectory at each time step.

- The magenta arrow indicates the swimmer Course Over Ground (COG): this is the net direction of swimmer movement, including current action.

- The dark purple arrow indicates swimmer heading: this is the direction in which the swimmer is producing thrust. Note that when the current goes completely slack, the magenta arrow and dark purple arrow become perfectly aligned.

Enjoy!

Constant $145^{\circ}$ Heading

Initially, I was curious to see whether there existed a simple, constant-heading solution that would deliver a swimmer moving at a constant pace to a desired destination (e.g. Lake Tashmoo). So I ran a few simulations, and found that a swimmer departing Nobska Beach at 6:18a on the morning of July 30th, 2022, who was able to hold an average 2:00/100yd pace, and a constant heading of 145 degrees, would have quite a pleasant, efficient swim. At nearly all points throughout the journey, the swimmer’s thrust vector is either perpendicular to, or somewhat aligned with, the tidal current vector (non-negative scalar product). This is ideal, as it means the swimmer is not “fighting” the current.

Unfortunately, this strategy places the swimmer directly in the Steamship Authority’s ferry lane for much of the journey across Vineyard Sound. Efficiency is a delightful thing, but truly nothing compares to the joy and satisfaction one feels when not being run over by a 154 ft ferry capable of producing 9,400 HP thrust, moving at 35 knots. We needed a different strategy.

Forced Transit Through Predefined Waypoints

Realizing that we needed to first cut southwest across the ferry lane (again, to avoid being run over), before pivoting southeast toward Martha’s Vineyard, we selected a set of waypoints that seemed like they would deliver us to our destination. Unfortunately, this resulted in a much longer swim, both in terms of distance and time. Following this strategy would also force the swimmers to fight hard against the current over Middle Ground, toward the end of the swim. Back to the drawing board!

Hybrid Strategy: Transit 1st Waypoint + Constant $140^{\circ}$ Heading

At this point, we had a fairly good idea of what we needed to do: we would transit across the ferry channel to the first waypoint as quickly as possible, and then pursue a constant-heading trajectory thereafter. So, I ran a 2D matrix of experiments, varying both departure time and swim pace.

I was quite concerned about the impact of fatigue. If a swimmer started slowing down somewhere in Vineyard Haven, I wanted to know exactly what might happen to them. This is why I ran both “fast pace” simulations (1:40/100yd) and “slow pace” (2:00/100yd) simulations.

As for the departure times, well… the Chappy Swimmers are a lovely group, but also a loquacious one! We like to chat before swims. Accordingly, I thought it might also be useful to assess the impact of punctuality (Incidentally, I think everyone was so nervous, we ended up departing Nobska Beach a minute or two early).

Here are the resulting six simulations:

6:00a Departure | 1:40/100yd Pace

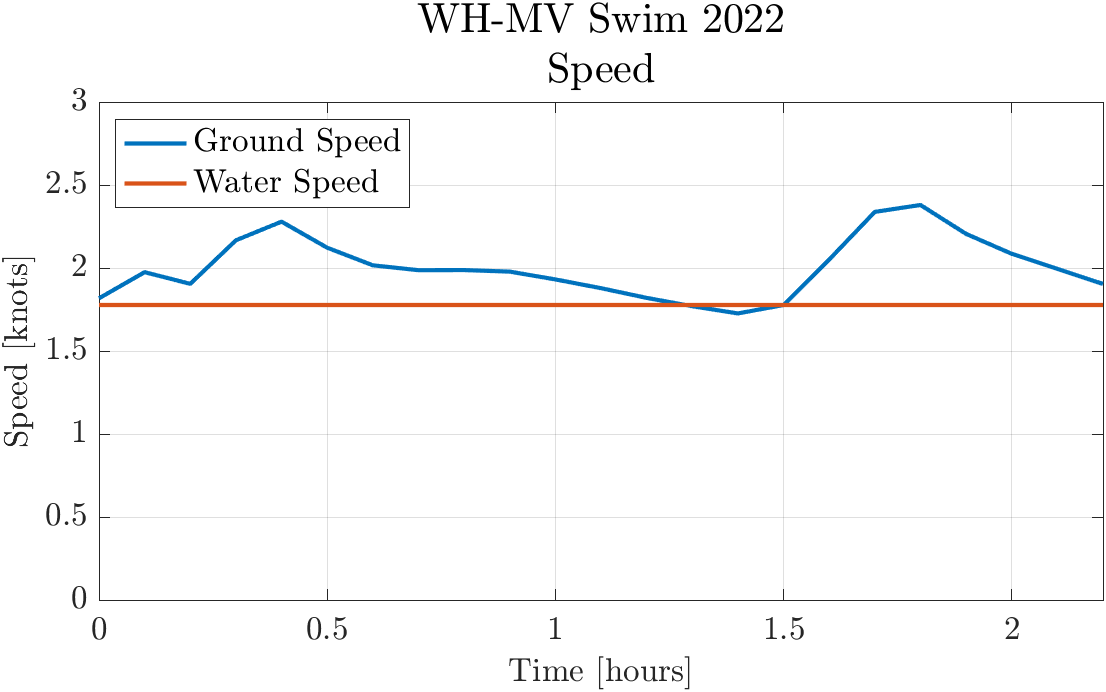

Swimmer speed over ground (SOG) and speed-through-water. Ideally, SOG should always be greater than or equal to speed-through-water, indicating that the swimmer is never fighting the current. In math terms, this efficiency condition is achieved by ensuring that that the dot product of swimmer velocity and current velocity is non-negative at each timestep. For this particular simulation, the efficiency condition is met at every time except $t=1.4~hr$.

6:00a Departure | 2:00/100yd Pace

6:18a Departure | 1:40/100yd Pace

6:18a Departure | 2:00/100yd Pace

6:30a Departure | 1:40/100yd Pace

6:30a Departure | 2:00/100yd Pace

Key Findings

I think more than anything, these simulations really underscore the extent to which timing is crucial for this swim.

While the tide is ebbing, a strong southwesterly current develops in Vineyard Sound, reaching maximum speeds of 3-5 knots, depending on the lunar cycle. The current then goes slack for a mere twenty minutes, reverses, and begins ripping back toward the northeast. In shallow regions of Vineyard Sound, like Middle Ground, the large volume of water being funneled between Woods Hole and Martha’s Vineyard can produce extremely fast local current velocities, and even hydraulic jumps. Obviously, these are not ideal conditions for swimming!

These simulations point to a useful conclusion: it is far safer and more conservative to err on the side of departing too early, as opposed to departing too late. Departing at 6:00a, instead of 6:30a, may result in a slightly longer swim, but also gives swimmers more wiggle room to contend with exhaustion, cramps, heading misalignment, and various other unforeseen circumstances.

I think simply visualizing how strong the currents can become (2-3 times our sustainable swim speed) gave the Chappy Swimmers a healthy dose of humility. These simulations helped us understand that we might have be a bit flexible if things didn’t go exactly as planned.

The Swim

The morning of the swim arrived, and the damp July air was buzzing with electricity. Amplified laughter betrayed jittery nerves. Beaming smiles were interspersed with heavy sighs and idle stretching. The mood felt vaguely schizophrenic and unstable. Each of the ten swimmers would occasionally gaze off into the distance, somehow both focused and vacant, contemplating the crucible that lay ahead.

![Sighing heavily while smiling, and also idle stretching. [Photo: Christie Hegermiller]](blake-stretch.jpg)

Sighing heavily while smiling, and also idle stretching. [Photo: Christie Hegermiller]

![Chappy Swimmers Blake Cole, Kalina Grabb, Karen Mareb, and Dina Pandya; along with support boat crew Kelsey Chenoweth and Captain Eve Cinquino. [Photo: Wan Grabb]](blake-friends.jpg)

Chappy Swimmers Blake Cole, Kalina Grabb, Karen Mareb, and Dina Pandya; along with support boat crew Kelsey Chenoweth and Captain Eve Cinquino. [Photo: Wan Grabb]

Fortunately, the conditions looked ideal: there was very little wind, and no waves. The sea surface was smooth and glassy. The water visibility was at least 15-20 feet, and the water temperature was in the neighborhood of $70^{\circ}F$. It seemed as though the sea gods had smiled upon our venture, and might see fit to deliver us safely across Vineyard Sound. Only time would tell.

At 5:58a, it was time to go: each swimmer took a final deep breath, their body weight still supported by the silty sands off Nobska Beach, and dove into the water. They would touch neither solid ground nor boat for the following two hours.

The swim itself was fortunately quite uneventful for seven out of the ten swimmers. We settled into a rhythm, and enjoyed the strange solace of gliding through an unfamiliar aquamarine world. Some of us tripped out a little. John mentioned that he felt like he was flying through the Cosmos, and my inner dialogue was dominated by a scientifically apocryphal mantra about humans being the descendants of whales.

![The ancestral placental mammal. [Credit: Carl Buell]](placental-mammal.png)

The ancestral placental mammal. [Credit: Carl Buell]

[Incidentally, I looked this up afterwards, an apparently we share a common ancestor, but are in no way the descendants of whales. Disappointing.]

The conditions remained favorable throughout the swim, and just after 8:00a, John McCadam arrived on the shore of Martha’s Vineyard, just north of Lake Tashmoo. Blake Cole, Meri Gilson, and Kalina Grabb made landfall a few minutes later, followed by Megan Titas, Dina Pandya, and Karen Mareb. Karen had endured a painful leg cramp during the last half of the swim. Nevertheless, she managed to persevere through the discomfort, and finished the swim using only her arms.

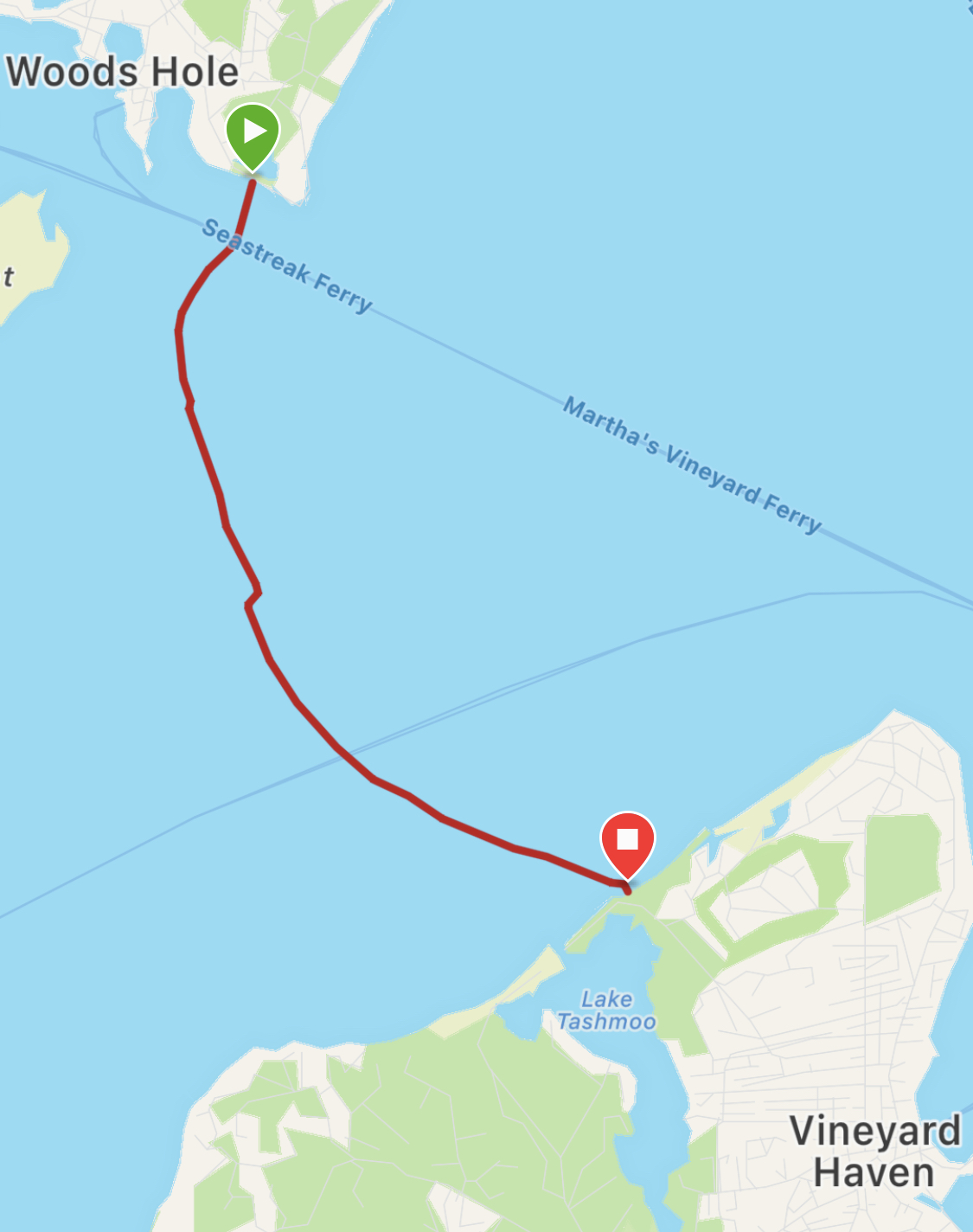

Swim path traversed by Blake Cole, recording using a Garmin Fenix 7S smartwatch, with multi-band GNSS mode enabled.

One of the most memorable aspects of the swim was the kindness bestowed upon us by the homeowners upon whose beach we landed. Having various preconceptions about Martha’s Vineyard and its mostly-too-affluent inhabitants, I had been expecting a chilly reception, at best. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The husband and wife who greeted us were named Tom and Casey, and they were the sweetest people ever: not only did they congratulate us, but they offered us hot coffee, water, and snacks. It was such a touching human moment, and meant so much to me!

But, as time drew on, the folks on the beach became increasingly concerned: three of the original ten swimmers remained unaccounted for, and could not be seen from the shore. Gazing out toward Middle Ground, small ripples had begun forming on the sea surface, indicating that the dangerous northeasterly current we had hoped to avoid was now rapidly building in strength.

At 8:30a, Rick Rheinhardt, Mary Kaminski, and Moira McCullough had still yet to arrive. With each passing minute, we understood that the northeasterly current would continue accelerating, eventually reaching a top speed of over 5 knots. Eventually, around 8:50a, reports came trickling in from support boats: the three swimmers had indeed become stuck in the current, and were still fighting hard to make it to shore. Fortunately, over an hour after John McCadam’s toes touched sand on Martha’s Vineyard, we received word that the trio had made landfall near the tip of West Chop Point, after swimming over 5.3 miles. This was an incredible feat of strength and determination – kudos to Rick, Mary, and Moira!

Conclusion

So, the question remains: how effectively did the ADCIRC model predict our swim trajectory?

Unfortunately, we will never know.

This question cannot be answered, because there is no way to determine the control effort exerted by each swimmer; in other words, while a GNSS track can tell us a swimmer’s speed over ground (SOG), course over ground (COG), and true position over time, these metrics do not distinguish the influence of the current from the effort exerted by the swimmer. This disambiguation would require knowledge of the swimmer’s true heading and speed-through-water during the swim.

Nevertheless, we can make a few observations, based on the data we were able to collect.

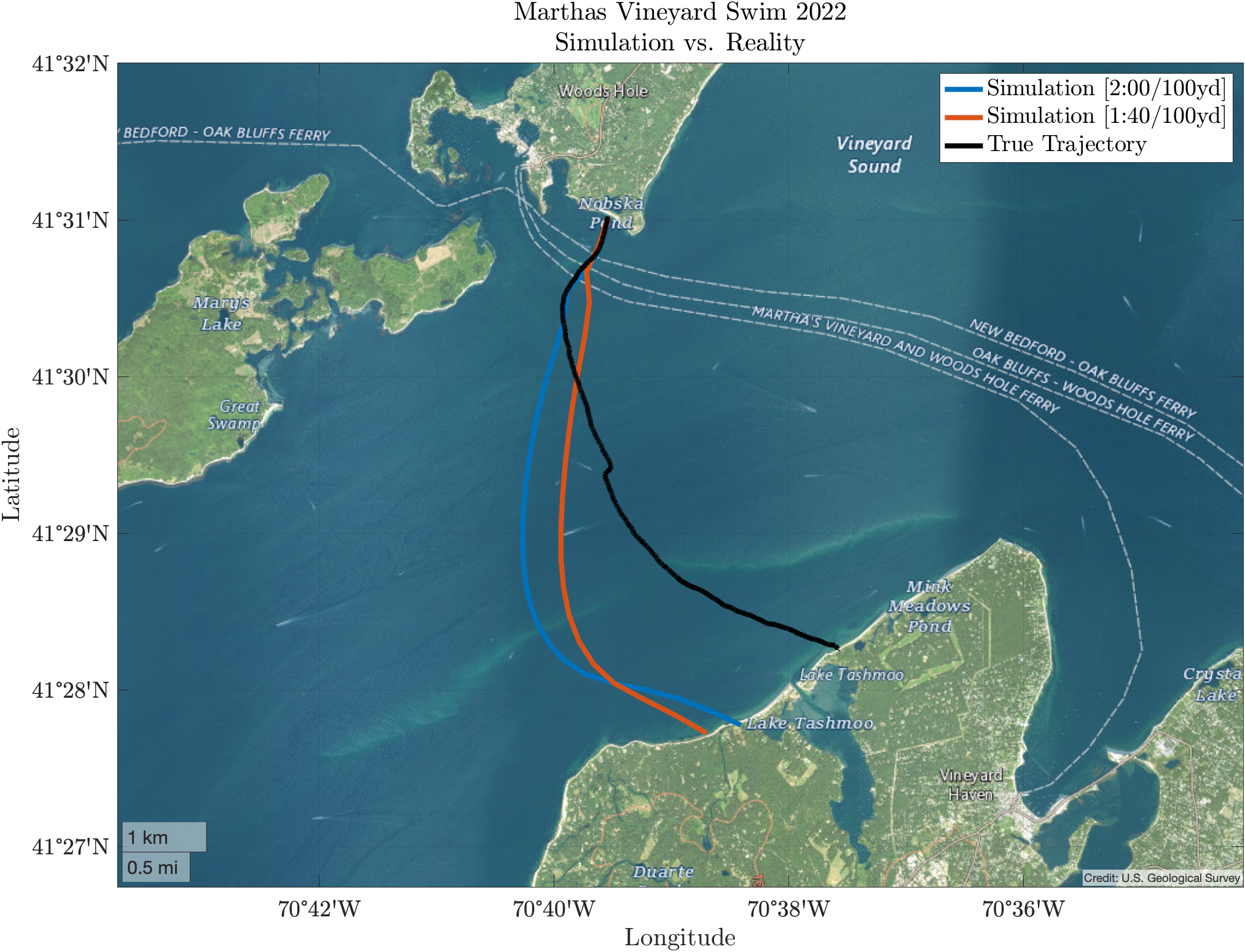

True swim path compared to simulations produced using the ADCRIC hydrodynamic model.

Immediately, it is clear that the path predicted by the ADCIRC simulations is significantly different than the true path traversed by the first wave of swimmers on July 30th, 2022. Why might this be? What might have led to this inconsistency? Allow me to propose a few hypotheses:

Hypothesis #1: Insufficient Bathymetric Resolution

As mentioned earlier in the Assumptions & Caveats section, it is possible that the coarse spatial resolution of the ADCIRC bathymetric data led to an underestimation of the northeasterly current that develops over Middle Ground during the initial stages of a flood tide. If this were true, the swimmers would be swept substantially farther northeast than the model predicted.

The data supports this hypothesis. One need only to observe the radical easterly deviation in trajectory that occurs just as the swimmers are passing over Middle Ground. Assuming the swimmers maintained a constant speed-through-water and heading, this deviation can almost certainly be attributed, at least in part, to stronger than expected tidal currents over Middle Ground.

Hypothesis #2: Heading Error

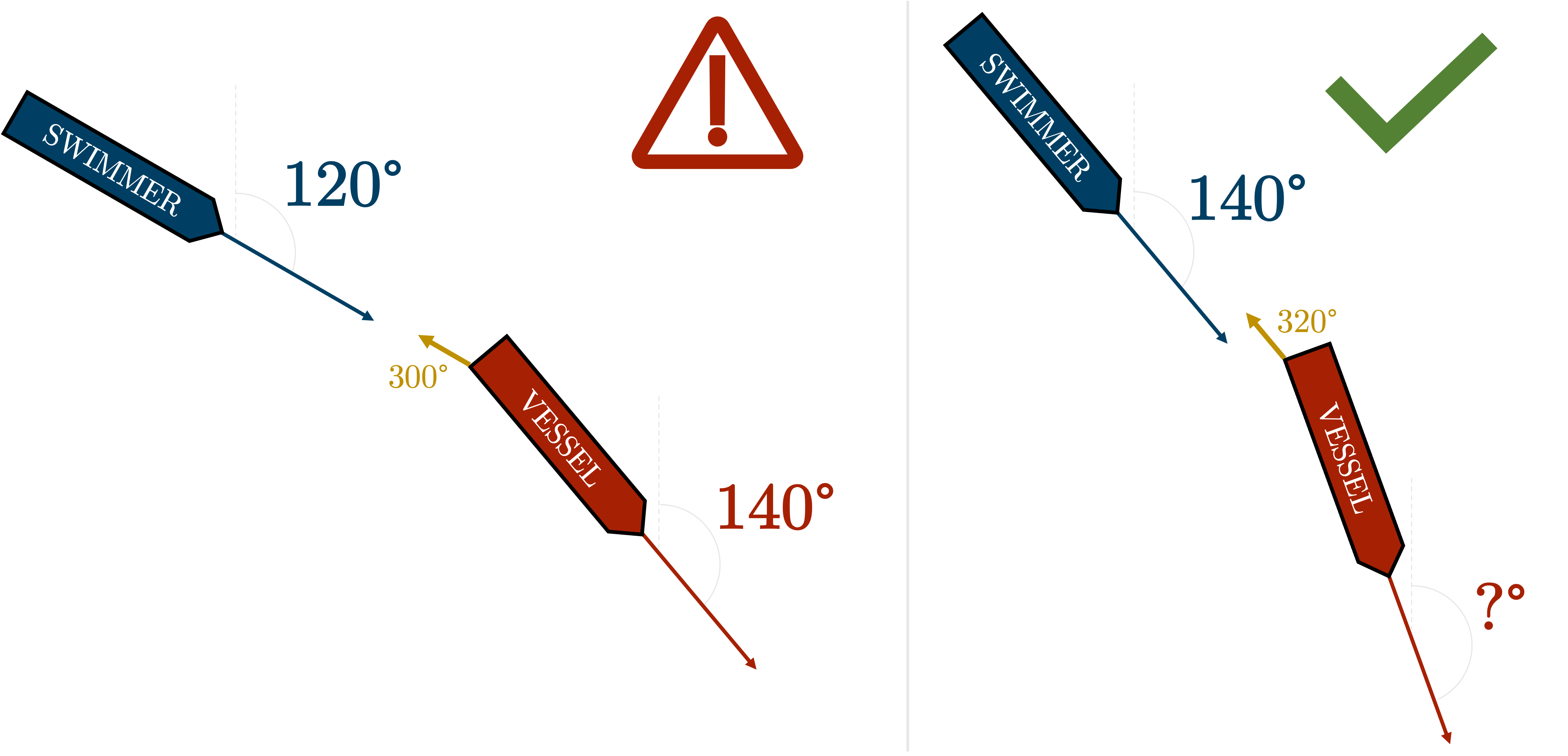

It is possible that the swimmers were not, in fact, following a $140^{\circ}$ heading. Lacking terrestrial landmarks, the “objective function” of each swimmer was simply to swim directly toward their guide vessel at all times. Thus, in order for the swimmers to remain on a fixed $140^{\circ}$ heading, their respective guide boats needed to maintain a $320^{\circ}$ relative bearing to them (say, using a handheld compass). This is a subtle, but crucial distinction: it is not the instantaneous heading of the guide vessel that matters, but rather, its relative bearing to the swimmers, measured with respect to true north. The figure below illustrates a situation in which a guide vessel is pursuing a $140^{\circ}$ heading, but is nevertheless inadvertently leading its swimmers in a more easterly direction.

Depiction of the importance of relative bearing between swimmer and support vessel. In the left-hand figure, the support vessel is following a $140^{\circ}$ heading; however, the relative bearing from the swimmer to the support vessel is $120^{\circ}$ ($-20^{\circ}$ offset from the target heading of $140^{\circ}$). In this scenario, the support vessel should observe that its relative bearing to the swimmer is $300^{\circ}$ instead of $320^{\circ}$, and begin clocking around to the right until the relative bearing reads $320^{\circ}$. This corrected configuration is displayed in the right-hand figure. Note that the instantaneous, absolute vessel heading is not relevant; only its bearing relative to the swimmers matters.

Rob Thieler suggested another potential source of heading error: magnetic declination. Indeed, in the vicinity of Vineyard Sound, there is a $14^{\circ}~13’~W$ separation between magnetic north (the direction a magnetized compass needle points) and true north (the direction along a meridian, towards the geographic North Pole). Many marine GNSS systems account for magnetic declination by default, but some do not, and it isn’t always easy to determine the active compass mode. Following a 140 degree bearing relative to magnetic north would place us on a 126 degree bearing relative to true north.

It is also possible that heading errors were simply inevitable. A propeller-driven ocean vessel moving at slow speeds (1-2 knots) has virtually no heading control authority. Holding a fixed bearing, relative to a moving school of swimmers, while contending with currents, wind, and waves is no easy feat. We were incredibly fortunate to have such experienced support vessel captains, and literally could not have completed this swim without them. A massive thank you to our captains: Chuck Redington, Robert Catilano, Eve Cinquino, Christie Hegermiller, and Kevin Manganini.

Regardless of the source of the heading error, the data seems to suggest that there was some heading error, for some reason. Roughly halfway through the swim, we took a brief break to hydrate. This break can be seen in the data, when the black line jogs slightly southwest. This small hop seems to suggest that the dominant tidal current in Vineyard Sound was still driving us southwest at this time, and had not yet gone slack. Yet, our course over ground appears to be approximately 140 degrees; this would imply that our instantaneous heading must have been something less than 140 degrees (more easterly) at this time.

In some ways, this is the most obvious explanation: pursuing a more easterly course will result in a path that is shifted in an easterly direction.

Hypothesis #3: Systemic Model Error

Finally, it is possible that the ADCIRC model is simply inaccurate, or lacks sufficient spatial or temporal resolution. However, given the strong consistency of its predictions with the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book, I think this is unlikely.

Conclusion II

Well, that just about wraps up this longer-than-expected blog post. If you have any questions, concerns, or alternative hypotheses regarding the discrepancy between the true swimmer trajectory and the path predicted by ADCIRC, please reach out. Thanks for reading.